-

chevron_right

chevron_right

Matthew Garrett: Investigating a forged PDF

news.movim.eu / PlanetGnome • 24 September • 6 minutes

This post is not about that.

Now, under Californian law, the onus is on the landlord to hold and return the security deposit - the agency has no role in this. The only reason I was talking to them is that my lease didn't mention the name or address of the landlord (another legal violation , but the outcome is just that you get to serve the landlord via the agency). So it was a bit surprising when I received an email from the owner of the agency informing me that they did not hold the deposit and so were not liable - I already knew this.

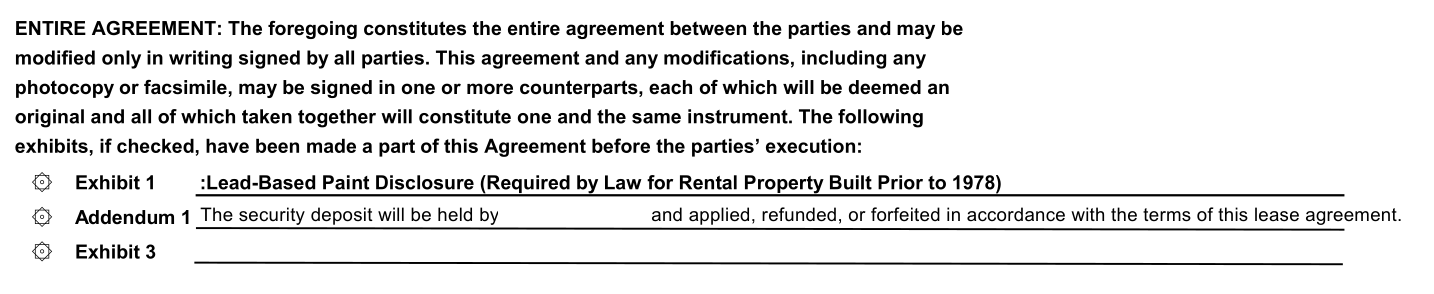

The odd bit about this, though, is that they sent me another copy of the contract, asserting that it made it clear that the landlord held the deposit. I read it, and instead found a clause reading

SECURITY: The security deposit will secure the performance of Tenant’s obligations. IER may, but will not be obligated to, apply all portions of said deposit on account of Tenant’s obligations. Any balance remaining upon termination will be returned to Tenant. Tenant will not have the right to apply the security deposit in payment of the last month’s rent. Security deposit held at IER Trust Account., where IER is International Executive Rentals , the agency in question. Why send me a contract that says you hold the money while you're telling me you don't? And then I read further down and found this:

Ok, fair enough, there's an addendum that says the landlord has it (I've removed the landlord's name, it's present in the original).

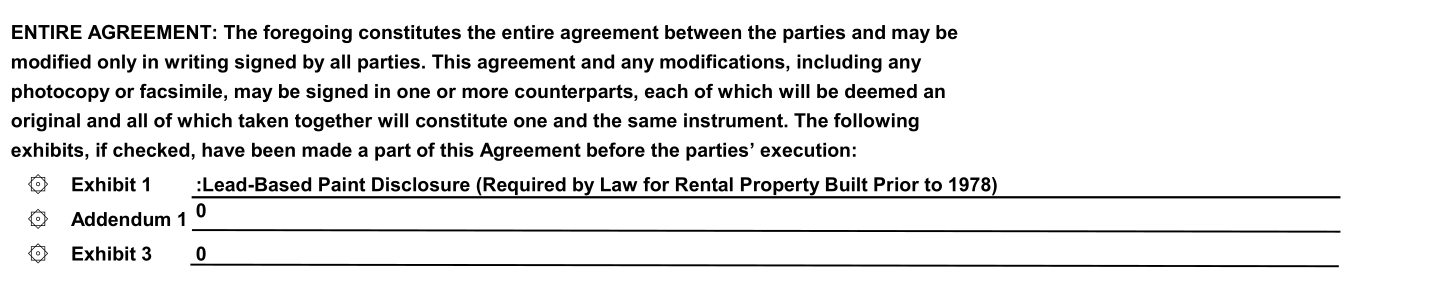

Except. I had no recollection of that addendum. I went back to the copy of the contract I had and discovered:

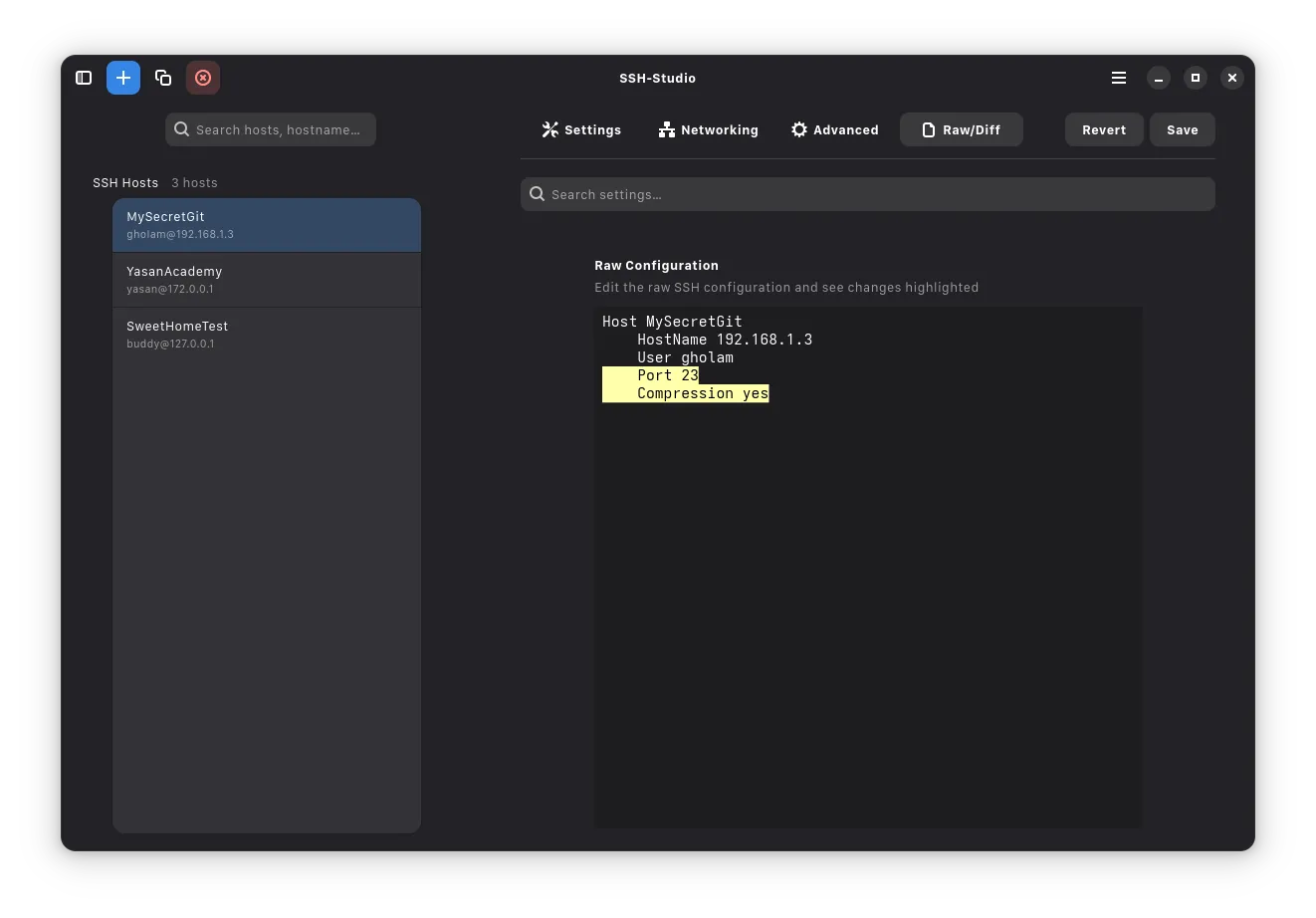

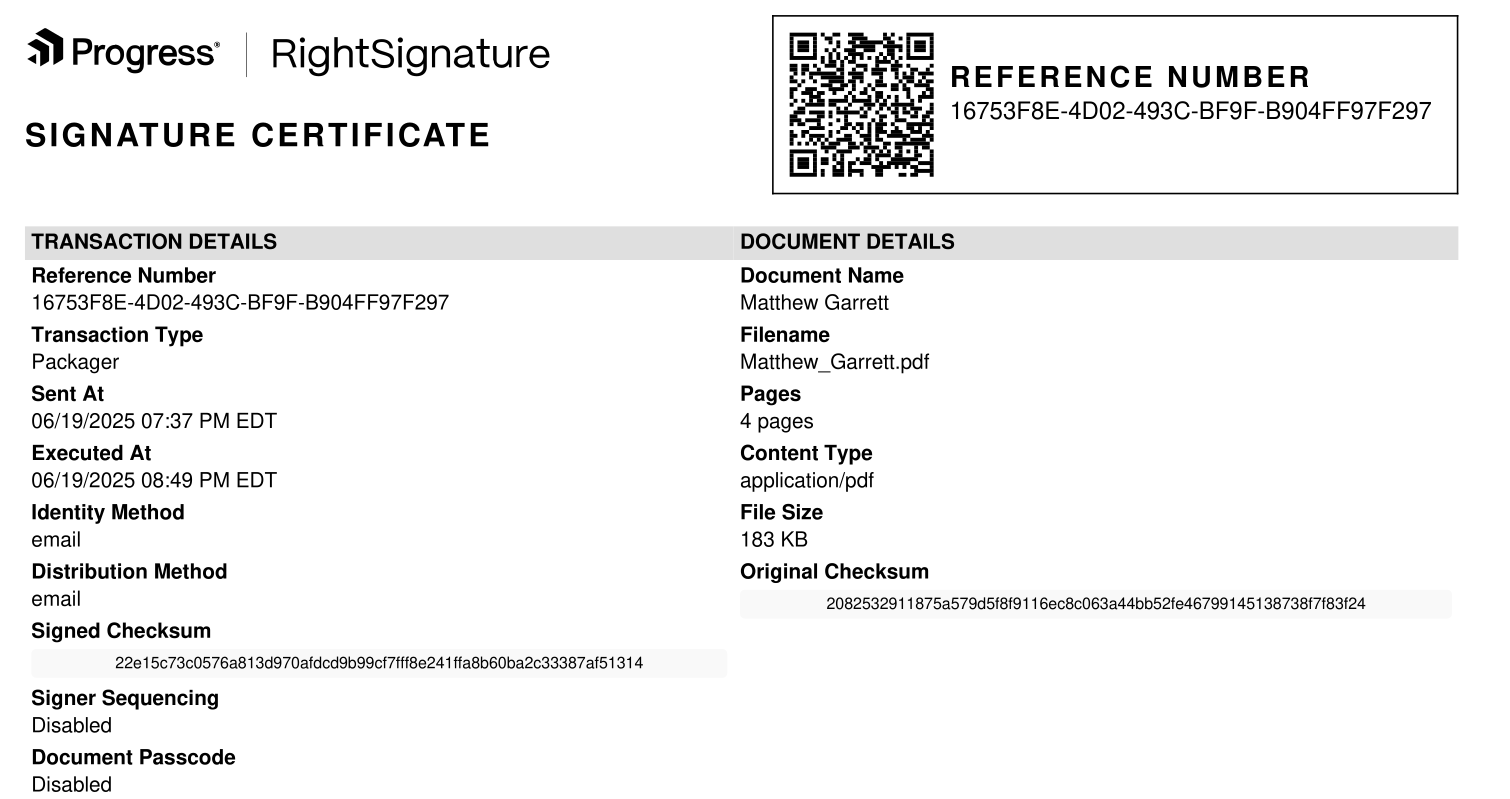

Huh! But obviously I could just have edited that to remove it (there's no obvious reason for me to, but whatever), and then it'd be my word against theirs. However, I'd been sent the document via RightSignature , an online document signing platform, and they'd added a certification page that looked like this:

Interestingly, the certificate page was identical in both documents, including the checksums, despite the content being different. So, how do I show which one is legitimate? You'd think given this certificate page this would be trivial, but RightSignature provides no documented mechanism whatsoever for anyone to verify any of the fields in the certificate, which is annoying but let's see what we can do anyway.

First up, let's look at the PDF metadata. pdftk has a dump_data command that dumps the metadata in the document, including the creation date and the modification date. My file had both set to identical timestamps in June, both listed in UTC, corresponding to the time I'd signed the document. The file containing the addendum? The same creation time, but a modification time of this Monday, shortly before it was sent to me. This time, the modification timestamp was in Pacific Daylight Time, the timezone currently observed in California. In addition, the data included two ID fields, ID0 and ID1. In my document both were identical, in the one with the addendum ID0 matched mine but ID1 was different.

These ID tags are intended to be some form of representation (such as a hash) of the document. ID0 is set when the document is created and should not be modified afterwards - ID1 initially identical to ID0, but changes when the document is modified. This is intended to allow tooling to identify whether two documents are modified versions of the same document. The identical ID0 indicated that the document with the addendum was originally identical to mine, and the different ID1 that it had been modified.

Well, ok, that seems like a pretty strong demonstration. I had the "I have a very particular set of skills" conversation with the agency and pointed these facts out, that they were an extremely strong indication that my copy was authentic and their one wasn't, and they responded that the document was "re-sealed" every time it was downloaded from RightSignature and that would explain the modifications. This doesn't seem plausible, but it's an argument. Let's go further.

My next move was pdfalyzer , which allows you to pull a PDF apart into its component pieces. This revealed that the documents were identical, other than page 3, the one with the addendum. This page included tags entitled "touchUp_TextEdit", evidence that the page had been modified using Acrobat. But in itself, that doesn't prove anything - obviously it had been edited at some point to insert the landlord's name, it doesn't prove whether it happened before or after the signing.

But in the process of editing, Acrobat appeared to have renamed all the font references on that page into a different format. Every other page had a consistent naming scheme for the fonts, and they matched the scheme in the page 3 I had. Again, that doesn't tell us whether the renaming happened before or after the signing. Or does it?

You see, when I completed my signing, RightSignature inserted my name into the document, and did so using a font that wasn't otherwise present in the document (Courier, in this case). That font was named identically throughout the document, except on page 3, where it was named in the same manner as every other font that Acrobat had renamed. Given the font wasn't present in the document until after I'd signed it, this is proof that the page was edited after signing.

But eh this is all very convoluted. Surely there's an easier way? Thankfully yes, although I hate it. RightSignature had sent me a link to view my signed copy of the document. When I went there it presented it to me as the original PDF with my signature overlaid on top. Hitting F12 gave me the network tab, and I could see a reference to a base.pdf . Downloading that gave me the original PDF, pre-signature. Running sha256sum on it gave me an identical hash to the "Original checksum" field. Needless to say, it did not contain the addendum.

Why do this? The only explanation I can come up with (and I am obviously guessing here, I may be incorrect!) is that International Executive Rentals realised that they'd sent me a contract which could mean that they were liable for the return of my deposit, even though they'd already given it to my landlord, and after realising this added the addendum, sent it to me, and assumed that I just wouldn't notice (or that, if I did, I wouldn't be able to prove anything). In the process they went from an extremely unlikely possibility of having civil liability for a few thousand dollars (even if they were holding the deposit it's still the landlord's legal duty to return it, as far as I can tell) to doing something that looks extremely like forgery .

There's a hilarious followup. After this happened, the agency offered to do a screenshare with me showing them logging into RightSignature and showing the signed file with the addendum, and then proceeded to do so. One minor problem - the "Send for signature" button was still there, just below a field saying "Uploaded: 09/22/25". I asked them to search for my name, and it popped up two hits - one marked draft, one marked completed. The one marked completed? Didn't contain the addendum.